In law and government, de jure describes practices that are legally recognised, regardless whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, de facto ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally recognised.

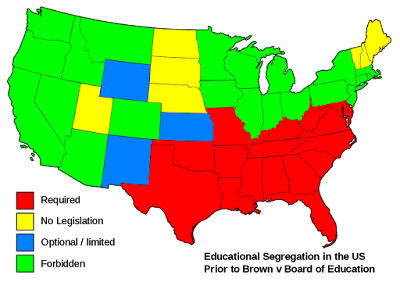

In U.S. law, particularly after Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the difference between de facto segregation (segregation that existed because of the voluntary associations and neighborhoods) and de jure segregation (segregation that existed because of local laws that mandated the segregation) became important distinctions for court-mandated remedial purposes.

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/6/28/19102496/biden-harris-busing-desegregation-google-data .

...

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that American state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Court's unanimous (9–0) decision stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal," and therefore violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. However, the decision's 14 pages did not spell out any sort of method for ending racial segregation in schools, and the Court's second decision in Brown II (349 U.S.294 (1955)) only ordered states to desegregate "with all deliberate speed".

.....

The Court's decision in Brown partially overruled Plessy v. Ferguson by declaring that the "separate but equal" notion was unconstitutional for American public schools and educational facilities. It paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the Civil Rights Movement, and a model for many future impact litigation cases. In the American South, especially the "Deep South", where racial segregation was deeply entrenched, the reaction to Brown among most white people was "noisy and stubborn". Many Southern governmental and political leaders embraced a plan known as "Massive Resistance", created by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd, in order to frustrate attempts to force them to de-segregate their school systems. Four years later, in the case of Cooper v. Aaron, the Court reaffirmed its ruling in Brown, and explicitly stated that state officials and legislators had no power to nullify its ruling.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.